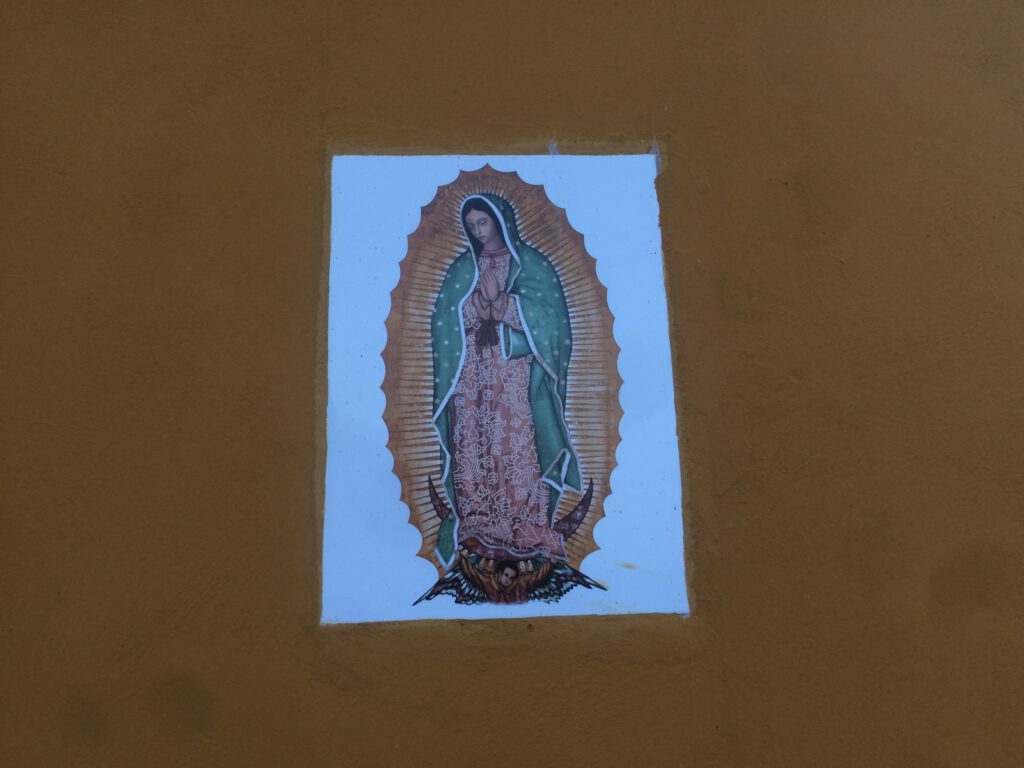

Learning things. It happens. Either by intent, by accident, or by bicycling around the Mexican town of (only-one-s) Progreso in the Yucatán. It’s a place that honours family, the citizens are quick to smile, and really cute children squeal at the pitch of peacocks. It has a modern culture that has slept in the shadows of the ancient pyramids built by its ancestors – and centuries later, live with the omnipresent 500 year old image of the Virgin of Guadalupe mounted on their doors.

Non-sectarian street art does exist here, but it seems to be philosophically outnumbered by the art-and-craft themed religious installations dedicated to the kindness and generous nature of the 16th century mother of god.

For millennia, natives of the Yucatán have survived the radical changes brought about by invasion, slavery, war, and cultural and spiritual appropriation.

Amongst all those factors, the pivotal event in Mexican history that completely redirected the spiritual course of this country was the miracle of “The Guadalupe Event” in 1531.

The Virgin of Guadalupe appeared to the indigenous Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, on the hill of Tepeyac, located north of Mexico City. (The reported number of apparitions is uncertain, and varies between two to five.)

She reveals herself to Juan Diego as “the Mother of the One True God” and requests that a basilica be built on the very spot where she was standing. To prove to a sceptical bishop that she had indeed miraculously appeared to him, the Virgin instructed Juan Diego to collect roses in his “tilma” (a type of apron) and carry them to the bishop. Juan Diego was to cast them out only once he stood directly before the bishop. Juan did what he was told. When the flowers fell to the ground, what remained on the cloth was the perfect imprint of The Virgin of Guadalupe. This event was enough to convince both the bishop and his growing flock of the veracity of the miracle, and it was this 600-year-old miracle that changed the nation.

According to regional oral traditions, prior to “The Guadalupe Event” and the establishment of the first Spanish colonial settlement in 1519, there already existed a “divine mother” or a “mother of the gods”. She was referred to locally as either Tonantzin, Coatlicue, Cihuacóatl or Tetéoinan, and pilgrimages to her temple on Tepeyac Hill were already a common occurence.

In 1521, after the Spanish defeat of the Mayans, and once the existing temple on Tepeyac Hill had been razed, a new Christian temple was built on the same location and re-dedicated to the “Our Lady of Guadalupe”. In effect, the conquerors successfully blurred the regional beliefs of the native population and replaced them with a similar, but a more powerful Catholic version. Syncretism was complete, and within 20 years, an unprecedented 9 million inhabitants had converted to Christianity.

Today, we are highly sensitized and often taken to task regarding cultural appropriation, so it can be chilling to read the homily delivered by Pope John Paul II in 2002 for the canonization of Juan Diego. Referring to “The Guadalupe Event” the Pope said, “. . . it meant the beginning of evangelization with a vitality that surpassed all expectations. Christ’s message, through his Mother, took up the central elements of the indigenous culture, purified them and gave them the definitive sense of salvation”. He went on to refer to “The Guadalupe Event” as, “a model of perfectly inculturated evangelization”.

Regardless of perspective, The Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe remains one of the world’s major centres of pilgrimage for Roman Catholics.

The conversion of Tonantzin, Coatlicue, Cihuacóatl or Tetéoinan into the The Virgin of Guadalupe, along with their shared images and symbols, all join to make it an easy bicycle pilgrimage between belief systems.

These devotional pieces were found primarily in Progreso and the surrounding area. It is always a joyful moment to spot and photo-document such regional, individual and sincere installations. These totems portray a sense of humility and human frailty, but also of love and support. It is a melancholy experience. It feels as though I am witnessing a Mexico that is leaving us.

To “read” these installations it is worth being familiar with the symbols associated with The Virgin of Guadalupe. They include: – The Virgin standing in the middle of the sun, this implies that she is more powerful than the native’s most powerful sun god,’Huitzilopochtl’; – she stands upon the moon, a symbol of the local god of night, insinuating that she is more powerful than their god of darkness; – since the indigenous gods stare with eyes wide open and straight ahead, the Virgin’s averted gaze insinuates that she is not a god; – she is being carried by an angel which is a symbol of royalty; – she is wearing a blue mantle with a gold border which also implies royalty; – her red dress is a sign of martyrdom for the faith and also of divine love; – the gold brooch around her neck is a symbol of sanctity; and – although the Virgin is obviously pregnant, the four-petaled flower, or flower of the sun, around her waist symbolizes her virginity.

Ve con Dios. . .

Tonantzin, Coatlicue, Cihuacóatl, Tetéoinan y La Dama de Guadalupe.